About the author

Dave Heaton has written about music for over thirty years, including for PopMatters, The Big Takeover, and his own website Erasing Clouds. He lives in Kansas City, Missouri, with his wife and two children.

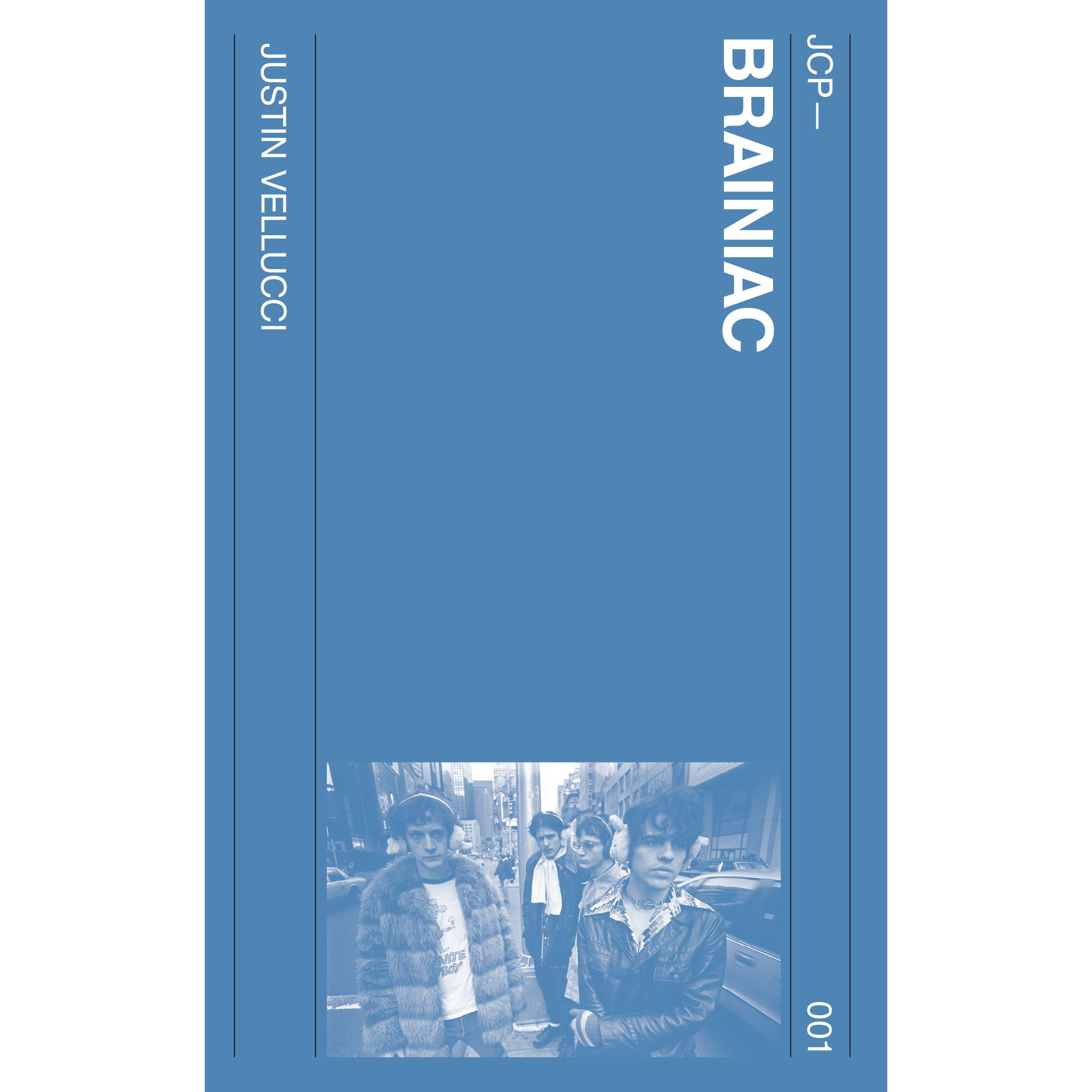

Photo by Chandler Johnson

-

Publication date: 7/11/24

ISBN: 979-8-9891947-2-8

Format(s): Paperback, ebook

Pages: 178

Size: 5x8

-

“De La Soul were one of the most uniquely, defiantly nonconformist groups to emerge in the creative free-for-all of the late eighties, not just in hip-hop but in any genre that valued fearless creativity. Heaton’s in-depth, career-spanning chronicle of their legacy doesn’t just get at what made their music special, but what motivated it—their upbringings, their enthusiasms, their influences, their friends (and rivals)—and in the process, he pinpoints in fine detail every giant step they took in evolving both their art form and their own relationship to a record business that might not have been entirely ready for them. A must-have whether you’re just starting to familiarize yourself with one of rap’s most transformative groups, or are a longtime fan looking for a reminder of just how and why they meant so much.”

—Nate Patrin, author of Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop

-

Chapter 1. Bigger than Me: An introduction

The graffiti writer tells his DJ friend that their art is about living for today: “Tomorrow’s a long way off, man. When I’m writing trains or when you’re mixing sounds, making people dance, that’s everything. We’re alive!”

That’s a scene from the movie Beat Street. Released in the summer of 1984, the same weekend as Ghostbusters and Gremlins, it was one of Hollywood’s first attempts to make mass entertainment (money) out of the New York City scene that by that point was the means of expression among young people living in the city and its surroundings—and had started spreading to urban youth across the United States. Beat Street was the Hollywoodized capitalization on Wild Style, the first hip-hop film. Filmed in ’81 and ’82, and released theatrically in ’83, that low-budget film was closer to the scene in every sense—starring real-life participants in the music, graffiti, and breakdancing scene of the time.

Hip-hop as a musical and cultural phenomenon is considered to have started in August 1973, with Kool Herc DJing his sister Cindy Campbell’s house party in the Bronx. A decade later, the country overall was waking up to its existence and turning it into a commercial proposition. In the early eighties, breakers were showing up in movies (Flashdance, Breakin’) and in TV commercials for products as big as Pepsi and McDonald’s. Breakers were treated as a novelty, but also represented a visual manifestation of the youth culture that had taken over New York City, the nation, and eventually the world.

About seven minutes in movie time after the “we’re alive” conversation, Beat Street’s graffiti writer character, Ramon “Ramo” Franco (played by Jon Chardiet), dies a tragic death on electrified subway tracks. The movie’s climax is a New Year’s Eve party turned memorial tribute for Ramo, with an atmosphere of both mourning and joy. The DJ character proclaims, “It’s not gonna be a funeral, it’s a celebration.” The scene was set and filmed at a club that the real musicians and breakdancing crews in the movie (Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, Treacherous Three, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Rock Steady Crew, New York City Breakers) knew well: the Roxy, which was located in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. The movie version of the club is the setting for a joyous memorial celebration. Blue-and-silver-robed gospel singers, led by Bernard Fowler, turn the club into church. The film’s main characters stand within a crowd on the stage. They laugh, hug, and dance through their tears.

March 2, 2023, a real-life event has a similar mixture of celebration and grief. Vincent Mason Jr., a.k.a. DJ Maseo of the rap trio De La Soul, is on stage at Webster Hall, in the East Village of Manhattan, about a mile and a half from where the Roxy once stood. Maseo is struggling to find the words to sum up how he feels, eighteen days after the death of fellow De La Soul founding member David Jude Jolicoeur, who went by Trugoy the Dove and then simply by Dave. “My emotions are very displaced,” he says. “My man is gone . . .”

That night Mason was surrounded on stage by friends: Kelvin Mercer a.k.a. Posdnuos of De La Soul, Prince Paul, Queen Latifah, Monie Love, Dres of Black Sheep, Common, Talib Kweli, Busta Rhymes, comedian Dave Chappelle, and more. Those individuals represented the sweep of De La Soul’s career and success, from their early singles in the late eighties through their status as influential mentors for a younger generation of artists.

The event was planned before Jolicoeur’s death at age fifty-four from heart failure shocked the hip-hop world. The night labeled the D.A.I.S.Y. Experience was intended to be sheer celebration. De La Soul’s first six albums were finally appearing on a music streaming service, that night at midnight, after two decades of legal and contractual battles eliminated the chances that new listeners would find their way to the group’s most significant recordings. The New Year’s Eve–style countdown was to a new era of availability, a world where De La Soul’s music had reemerged from the void.

It wasn’t easy for the now-duo of De La Soul—Mercer and Mason, Posdnuos and Maseo, Plug 1 and Plug 3—to get in a celebratory mood for the occasion. In a July 2023 video interview with Lyndsey Parker of Yahoo Entertainment, Mason gave Mercer credit for pulling him out of his funk and convincing him that the show must go on. “He came up with the greatest idea that I thought was perfect. ‘He was our Ramon. . . . We need to celebrate this, like the New Year’s Eve party in Beat Street.’”

In the week leading up to the D.A.I.S.Y. Experience, it was reframed as a tribute to Dave: “Join us to celebrate the life and legacy of Dave aka Plug 2 and De La Soul.”

Dave’s death, and the De La Soul streaming launch, came during a commemorative year for hip-hop: nominally the fiftieth year of the genre, counting back to Cindy Campbell’s house party. The first public, or at least televised, celebration was February 5, 2023, at the Grammy Awards, seven days before Dave’s passing. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of the Roots organized a fifteen-minute roller-coaster ride through the genre’s history, from Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five to Lil Uzi Vert. Each artist had thirty seconds or less to perform one of their classic songs.

Somewhere in the middle of the segment, soon after Public Enemy left the stage—at just about the right time chronologically—the backdrop turned to bright, fluorescent flowers and Posdnuos emerged in front of them, performing about twenty seconds of De La Soul’s “Buddy” before passing the mic to Scarface. It was a meaningful inclusion for a group that was getting ready to emerge from a state of semi-invisibility. Both Dave and Maseo missed the event for health reasons. Before that was public knowledge, theirs was a glaring absence for such a long-running unit.

How many musical trios can you think of that stuck together for over thirty years with no public breakups or squabbles? Take the odds against that type of longevity, and add to them the risk factors of youth, the newness of their genre, and the historical inequities of the music industry—the sheer number of young Black artists taken advantage of by corporations, across genre and era.

In that light, De La Soul has carried the aura of an indestructible force bonded by friendship, creative freedom, eccentricity, and loyalty. It started with kids in school finding common ground in their exploration of a still-new musical art form, so new that at first it wasn’t even thought of as a genre. They navigated overnight success, high-profile lawsuits, industry shenanigans, media stereotyping, the grind of exhaustive touring, and many other challenges. They grew De La Soul into a rock-solid partnership with a unique artistic legacy.

Even after Dave’s passing, De La Soul lives on. Since that event in March 2023, the duo has been on an ongoing celebratory/memorial tour. In 2023 alone, even amid the shock of tragedy, De La Soul played Coachella with Gorillaz, toured with Wu-Tang Clan & Nas on the NY State of Mind tour, collaborated with Robert Glasper at the Blue Note Jazz Festival of Napa Valley, performed at some dates on the commemorative F.O.R.C.E. tour, and handled publicity around the rerelease of their music.

In the Yahoo interview, Maseo declared, “Every member has to actually die before this thing can be over.” Posdnuos rhymed something similar in 2004 on the song “Rock Co.Kane Flow”: “We De La to the death or at least until we break up.”

In the Beat Street memorial scene, a photo of Ramo shows him standing next to a graffiti piece with the words: “It’s Bigger than Me, I Just Can’t Stop.” That sentiment is reminiscent of the work ethic driving De La Soul to continue, for over thirty years and onward into the future, even after tragedy and struggle. It brings to mind the continuum of Black creativity that led to De La Soul, from the records in their parents’ collections through to the earliest experimenters that spawned hip-hop culture and music.

The story of De La Soul is bigger than the trio themselves, even if you look just at the music. Their approach was rooted in collaboration at every step of the way: their dialogue with the ghosts of past artists and performers through sampling, their working partnerships with like-minded musicians. The community those collaborations created opened up new possibilities within the genre and beyond.

Their story is about loyalty as an overriding principle, creativity as the foundation for friendship (or vice versa), and resilience within the roller coaster that is the music industry. It is the story of a drive to keep something good going until the last possible moment.

I come to this story as one small speck within a galaxy that expands outward in many directions. I turned fifty the same month that hip-hop did. I grew up in the near-suburbs of St. Louis, Missouri, and am one of the white listeners who learned about the music after it was commercialized enough to reach me, via the channels of radio, MTV, and word of mouth. I borrowed LL Cool J and Run-D.M.C. tapes from elementary school classmates. I watched Yo! MTV Raps with host Fab 5 Freddy every Saturday morning, recorded it, and rewatched it. On Friday nights I listened to a rap radio show (African Alert, KDHX) when my classmates were at sporting events. I would ride my bike to one of two record stores (one for new, the other for used) to buy rap cassettes. I was one of the teenagers whose parents Newsweek was trying to scare with its 1990 cover story “Rap Rage,” which declared, on the cover, “Yo! Street rhyme has gone big time. But are those sounds out of bounds?”

“Why do white people like De La Soul so much?” a Black co-worker at my summer job asked me in 1990. Ice Cube was her favorite. I don’t think I had a good answer. This book will point toward a few: the way the group was marketed by their record label, the music they sampled, their suburban background, the way the “concept album” construction inadvertently plays into the hand of rock listeners used to thinking about albums in that way.

What first struck me was the lo-fi “Potholes in My Lawn” video, where they seemed to be just hanging out and speaking in code. At that time, I was eagerly soaking up rap music of all types, but De La Soul’s eclectic sampling and off-kilter personalities especially resonated with me, a kid who through radio listening, tape collecting, and library checkouts was trying to hear it all, the history of music, and get beneath its surface.

De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising contained a music history lesson, or at least a time-traveling tour, built into it. Its aesthetic echoed with other childhood interests, comic books and role-playing games. But I never thought of the music as sixties-ish, or De La Soul as “hippies.” They seemed as much a part of hip-hop culture as Eric B. & Rakim, MC Lyte, Boogie Down Productions, or any of the other artists I was fascinated with, who each brought their own style.

There are numerous books lying in wait within the story of De La Soul, including how-to lessons in agility, perseverance, innovation, and problem-solving. Their story connects with the stories of many other hip-hop artists, movements, and events—some of which will be partially told here. Above all, this is a book about how young creatives managed to build their fascination into fun, their fun into art, and their art into a professional career that built a legacy for the ages.